Campbell’s soup

When Andy Warhol painted Campbell’s soup cans in 1962, he had been inspired by popular culture and was representing the success of canned food. In fact he was depicting one of the most innovative ways to preserve food at that time.

Humans started preserving food a long time ago, when they discovered that some processes could make food last for longer without getting spoiled or rancid. Drying, salting, smoking, freezing and heating represent some examples.

Dried spaghetti

Drying

When cooking spaghetti, we don’t usually think of it as dried food. Drying is a crucial step in the pasta production process, where humidity, air flow and temperature are carefully controlled.

Arabs, not Italians, were the first to treat pasta by drying it, so they could eat the product any time during their desert wanderings. The first historical records of dried pasta production date back to the 11th century in Sicily, a southern Italian region deeply influenced by Arab culture at that time.

The master smoker lights the traditional red brick kilns at John Ross Jr, the Aberdeen producer of Scottish smoked Scottish salmon - Photo credits: John Ross Jr

Smoking

After discovering that meat cooked with fire was much more edible and tasty, humans realised that smoking could preserve foods from perishing, due to deposits of certain substances present in the smoke.

Oak and beech are the most used wood types for smoking. When burning, they generate antioxidant and antimicrobial compounds such as phenols and carboxylic acids. The smoking process can take place at a temperature below 24°C (“cold smoking”) or around 70°C (“hot smoking”).

Recently, the high costs and timing associated with traditional smoking along with concerns over phenols and other carcinogens have favoured the introduction of liquid smoking. This method consists of adding a cold aroma or injecting liquid smoke into the meat, thus not diminishing the bacterial load and therefore lowering the shelf life.

Food in glass jars

Canning

Canning is a method which extends a food’s shelf life typically from one to five years, or even more. The food is processed and sealed in an airtight jar or can and then sterilised by heating to a temperature that destroys microorganisms and inactivates enzymes. Heating and later cooling form a vacuum seal which prevents other microorganisms from recontaminating the food within the jar or can.

This method goes back to 1795 when Napoleon offered a prize to anyone who could invent a way of preserving food for his army and navy. In 1809, Nicolas Appert, a French confectioner and brewer, won it after discovering that if food was heated and then sealed in glass jars, it would not spoil.

Based on Appert's methods, Peter Durand, an English merchant, introduced tin cans in 1810. The reason why food didn’t spoil was unknown at that time. Fifty years later Louis Pasteur demonstrated the role of microbes in food spoilage.

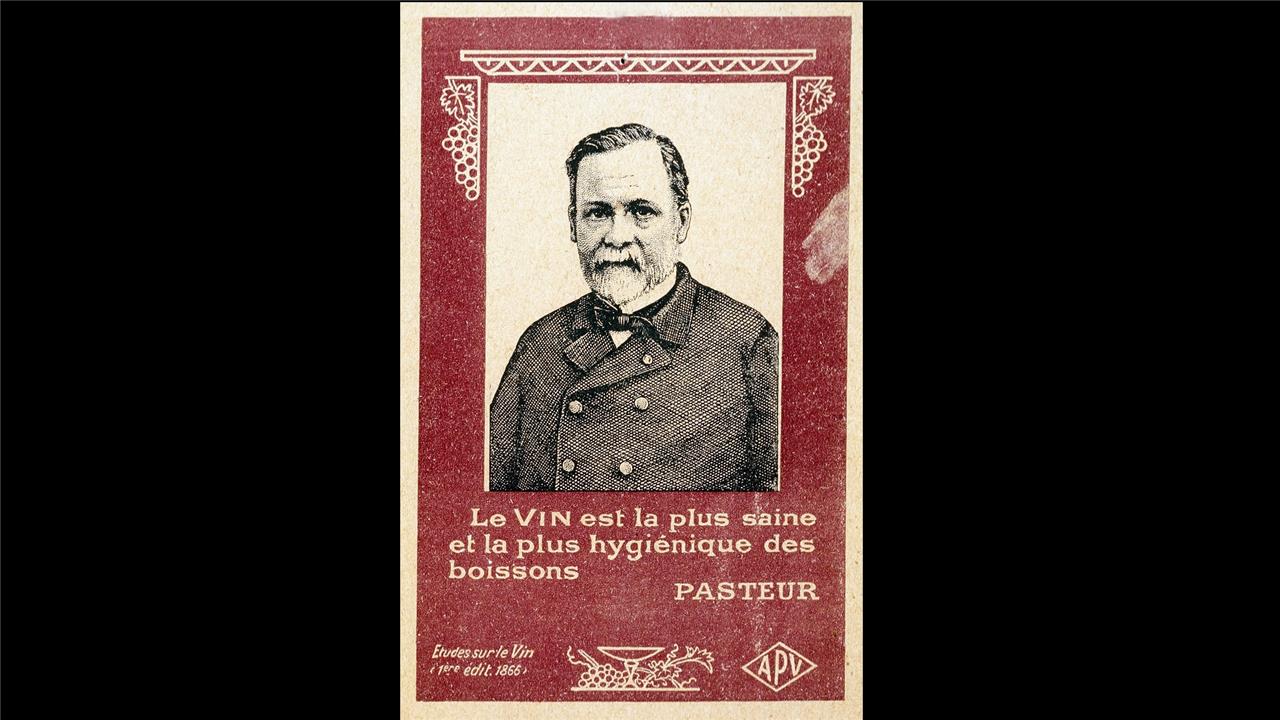

Louis Pasteur (© Institut Pasteur - Musée Pasteur)

Pasteurisation

Pasteurisation was invented by the French chemist Louis Pasteur in 1862. At the time, producers of French wine, which was being exported throughout Europe, were trying to find ways to preserve their precious beverage. Half of the wine had usually spoiled after a week or so.

After discovering microbes, Pasteur wanted to find a way to kill them without changing the taste of the wine. Boiling was not a solution.However, he did find a process whereby the wine could be heated to about 60°C for 10 minutes without any adverse effects.

Wine pasteurisation was only used for 10 years, until Pasteur discovered that if the wine barrels were cleaned with sulphur once a year, microbes would be kept away.

Beer pasteurisation followed and, many years after Pasteur’s death, the process was used to kill the pathogen microbes in food and drink such as milk, juice, and canned food.

Unlike sterilisation, the food is heated to about 50-70°C for 15 to 30 seconds and then quickly cooled to 10°C. This prevents the remaining bacteria (such as lactobacillus) from growing while maintaining taste and vitamins. This is why pasteurised milk has to be stored at 4°C.

Milk

Ultra-high temperature processing (UHT)

Ultra-high temperature processing is the most common technique to obtain shelf-stable milk. If pasteurisation requires heating at 55-70°C for a few seconds, UHT processing requires boiling at 135°C for 2-5 seconds.

Milk can then be preserved for 4-5 months at room temperature. All dangerous microorganisms are destroyed. But also vitamins.

Frozen raspberries - Photo credits: Sergey Kukota

Freezing

Refrigeration to preserve food dates back to prehistoric times, when people used snow and ice to store products. The commercialisation of frozen foods started in the 20th century in the US, using a rapid freezing method: deep freezing.

This industrial process quickly exposes food to temperatures from -30°C to -50°C, until the product core temperature reaches -18 ° C. The water contained in the food cells becomes finely crystallised, cells become “dormant” and the proliferation of microorganisms is limited. The product retains its freshness, texture, flavour and essential nutrients and vitamins.

This is not the case with home freezing, where the temperature drops slowly. From the water contained in foods, large ice crystals form and break the food cell wall thus altering texture and flavour.

Freezing cannot destroy all the microorganisms present in a food, but it can stop them from reproducing. The so-called cold chain is a series of activities maintaining food within a low temperature range from production to distribution. If the chain is broken and the food temperature rises above -18°C, bacterial growth starts again and the food is no longer preserved.

High Pressure Processing technology started its industrial evolution hand in hand with the avocado processing industry

High Pressure Processing (HPP) or Pascalisation

High Pressure Processing (HPP) or Pascalisation, is a technique by which packaged food products are put under very high pressure (6,000 bar or 600 MPa or 87,000 psi - pounds/square inch) applied by water for a few minutes (3 or less) at cold (4-10°C) or room temperature.

This process inactivates all microorganisms (bacteria, virus, yeasts, moulds and parasites) present in the food, considerably extending shelf life and guaranteeing food safety. Although invented in the 19th century, pascalisation was only developed on an industrial scale from 1990.

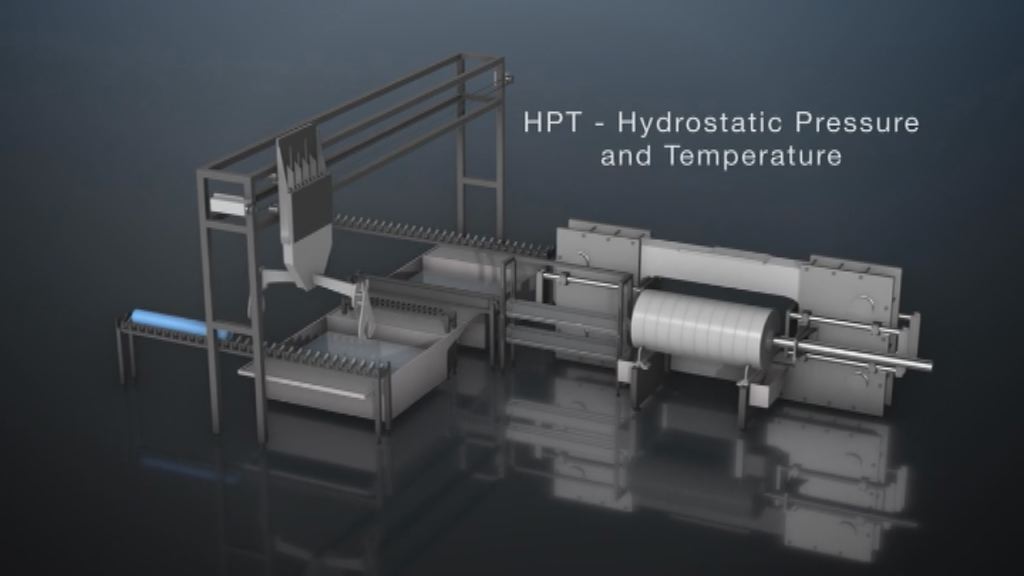

HPT technology

High Hydrostatic Pressure in combination with Temperature (HPT)

While HPP maintains a food’s freshness, flavour, texture and nutrients, and at the same kills the microorganisms present, High Hydrostatic Pressure in combination with Temperature (HPT) should represent a further improvement by combining preheating with high pressure. The HPT technique has not yet been applied on an industrial level, and it has been tested under the European HIPSTER project.

Rudi Vogel, a microbiologist and food technology researcher at the Technical University of Munich, who is collaborating with the project, told youris.com: “Now if you want to make shelf stable food you need 120°C for 20 minutes, if you go a little bit lower and you tolerate some rare spoilage events – say you do not transport your can to a warm country – then you can say 120°C for 5 minutes is the standard industrial process. I think if we combine temperature with pressure we can reduce it to a minute and even have lower temperatures”.